Colonialism + Identity – Part 3

Colonialism + Identity – Part 3

Introduction

This blog is part of a three-part series on colonialism and identity. Click here to see Part I: Legal Control of Identity or Part II: Standardization and Dehumanization.

What does an Indigenous person look like? What do they sound like? Do they have specific careers? Do they live in a different place? A wider impact of colonialism on Indigenous identity is all the different stereotypes of “Indian” identities and behaviours that it has created. In this post, I will reflect on behaviours classified as white or “Indian” by colonial spectators. I will also draw on my experiences growing up with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations.

Ideas of “Indianness” and Whiteness

In the time of “truth and reconciliation,” we have been encouraged to self-identify and be proud of our Indigenous identity. However, when I was younger, that was not the case. The ideas of “Indianness” and whiteness still held weight. There are times when I am still nervous to “out” myself as an Indigenous person. I am unsure of how to act, or if my actions will be perceived differently after people know I am Indigenous.

Under the restrictions of the Indian Act, social sanctioning by non-Indigenous Canadians, their police services, and their court systems characterized behaviours differently depending on whether the person exhibiting them was Indigenous or non-Indigenous. Racist legislation formed ideas about what “Indianness” looked like and how that was different from whiteness.

In addition to not being able to vote and being excluded from most universities, Indigenous peoples could not gather in groups larger than three. They could not hire a lawyer for land disputes, and they could not legally drink. So while John A. MacDonald could grip a desk in the house to stop him from drunkenly falling over, or throw-up during a public debate, an Indigenous man could not legally go to a bar after work. What this law did was perpetuate the stereotype of the ‘drunken Indian.’ While many people of different classes and colours have issues with alcohol, the law singled Indigenous people out. Although Inuit, Métis, and non-status peoples are not under the Indian Act, many of them faced this same oppression because they were visibly Indigenous.

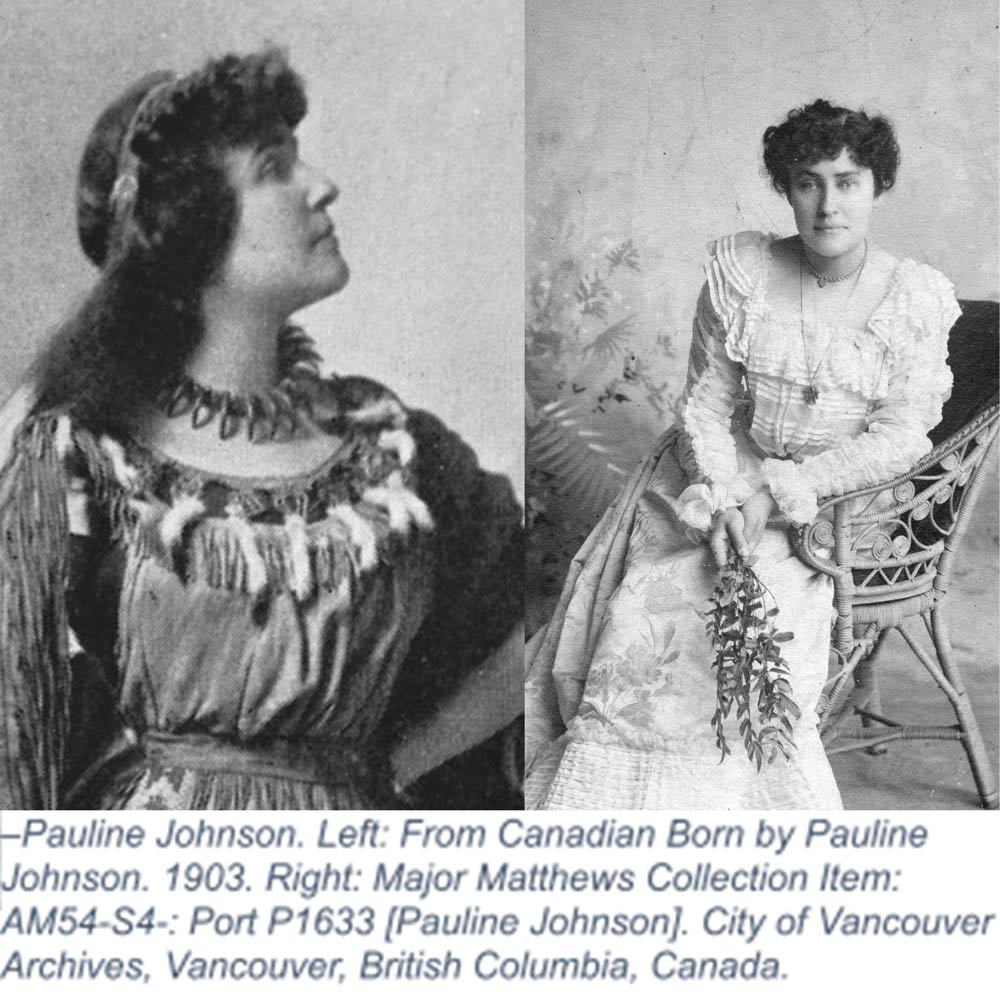

Stereotypes of “Indianness” put Status and non-status Indigenous people up against standards of whiteness. Poet Pauline Johnson showed these stereotypes in her performances where she would change into inauthentic “Indian” dress before switching to white colonial clothing. She did this to challenge racist ‘scientific’ views of the time and highlight the injustices faced by Indigenous women in colonial society. Johnson’s transformations were meant to show how we are the same people. It was an attempt to humanize Indigenous identity within the colonial perception of that time. However, this performance made for white audiences was interpreted differently. Her stage acts implied that Indigenous women could be assimilated into the dominant society just through clothing and behavioural means. If Johnson could walk away from the traditional outfits and reserve life towards formality, the rest of the “Indians” could do the same. White Canadian society at this time began to form an identity of the “successful Indian.” An Indigenous person who has assimilated to become a “productive” member of Canadian society. The key part of this transformation is leaving behind what is thought of as “Indian” behaviour.

“Successful Indians” gained prosperity or Status in the white world by adopting white characteristics of success—through language use, clothing, relocation, or formal education. Today, “successful” Indigenous peoples hold graduate, professional, or medical degrees and some work in Canadian politics. However, many of us who hold these positions have jealous white peers who remind us that a diversity quota secures our place. Or we are asked to share our traumas to solidify our authenticity in the colonial perception of the dysfunctional “Indian” identity. Some who find success in colonial institutions face a level of removal from our communities.

When non-Indigenous Canadians describe an Indigenous person, many stereotypes come to mind. They often have a manufactured idea of what we are supposed to look like and how we act. I tutored many newcomer and exchange students during my time at Algoma University who were surprised to learn I was Indigenous. One student told me their guide warned them that “Indigenous homeless people would scam and rob” them in Sault Ste. Marie. While it is true that Sault Ste. Marie has many homeless Indigenous peoples, this is due to the community history of residential schooling, not an Indigenous inclination towards crime. But newcomers and exchange students did not have this context.

Because half of my family is non-Indigenous, I heard these stereotypes and ideas about Indigenous identities from their perspective. My father had issues with the law and was in the prison system, and my mother’s family was worried about the effect this would have on my opportunities. Because I can pass for white, I was encouraged to do so. I was also encouraged to identify with white history and behaviours that would protect me from colonial perceptions about my abilities. When teachers learned about my “Indian Status Card,” I was treated differently, and all my faults were associated with Indigenous identity. When I was too loud, I was dangerous and disruptive instead of enthusiastic or passionate. While other students went into STEM or university prep courses, teachers told me I would likely go straight into the workforce. It was not until a history teacher in grade 10 encouraged me to change my classes to university prep that I imagined myself in the academic world.

Wrapping-up

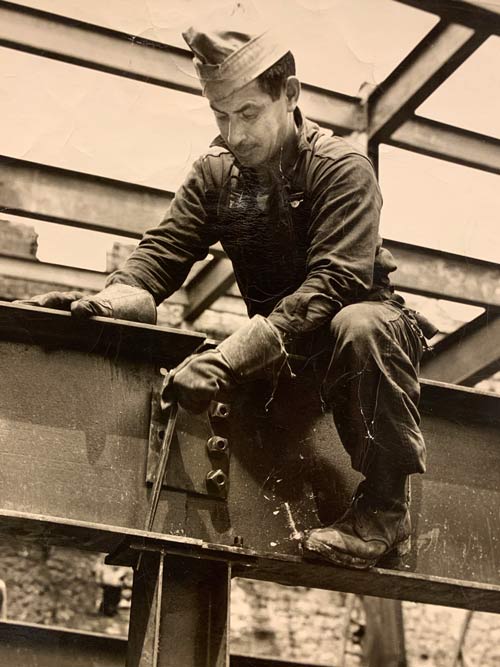

Because all lands in Canada are Indigenous lands—including cities and subdivisions—my father’s community adapted to, and thrived in, a new way of life. My ancestors built steel skyscrapers and bridges for Canadian and U.S. cities, and my father still builds critical infrastructure in Quebec. While it looks different from “traditional” notions of Indigenous identity created by colonial ideals, we still see ourselves in the land, urban cityscapes, and formed concrete. That’s because contemporary Indigenous identities are complex. Breaking behaviours up into “Indian” and “white” does not allow us to define ourselves.

Because all lands in Canada are Indigenous lands—including cities and subdivisions—my father’s community adapted to, and thrived in, a new way of life. My ancestors built steel skyscrapers and bridges for Canadian and U.S. cities, and my father still builds critical infrastructure in Quebec. While it looks different from “traditional” notions of Indigenous identity created by colonial ideals, we still see ourselves in the land, urban cityscapes, and formed concrete. That’s because contemporary Indigenous identities are complex. Breaking behaviours up into “Indian” and “white” does not allow us to define ourselves.

The colonial perception of what it means to be Indigenous are the leftovers of over a century of settler interference. It has left us with a popular image of Indigeneity that does not reflect all of us. Canadians need to understand where their ideas about Indigenous people come from and ask themselves if their understanding of Indigenous identity is a stereotype created by colonialism.

Colonialism has controlled the image and freedom of Indigenous identity for long enough. Power is shifting. The construction of identity for Indigenous people is moving from the Canadian state’s control to Indigenous peoples and nations themselves.

Thank you for following this blog series! Check-out more from Know Indigenous History on our new website. Follow Skylee-Storm on twitter @storm9115 or send them an email, skylee-storm@knowhistory.ca.

Disclaimer: While Canada and their governments have recommitted to “reconciliation,” equity, and diversity, colonialism is still with us: it just looks different. Today’s colonialism looks like higher arrest rates, higher dropout rates, higher suicide rates, child removal, poor infrastructure, and unsafe drinking water. All these things still impact Indigenous identity regardless of apologies or acknowledgements.

Skylee-Storm Hogan (Stacey) is a public historian who focuses on Residential Schools history, Indigenous legal history, and community-based archival practice. Skylee-Storm is a graduate of Western University’s Master of Public History program and began working with Know History as a Research Associate in 2019. They have recently completed a micro-documentary on the Quebec Bridge Disaster of 1907 and the impacts faced by their ancestors and the Mohawk community of Kahnawake.

Skylee-Storm Hogan (Stacey) is a public historian who focuses on Residential Schools history, Indigenous legal history, and community-based archival practice. Skylee-Storm is a graduate of Western University’s Master of Public History program and began working with Know History as a Research Associate in 2019. They have recently completed a micro-documentary on the Quebec Bridge Disaster of 1907 and the impacts faced by their ancestors and the Mohawk community of Kahnawake.

Recent Posts

Visit with the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia

During Black History Month, Know History was honoured to welcome members of the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, alongside invited cultural and museum leaders, to our Bank Street office for an afternoon of conversation, connection, and shared learning.

Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke

We are proud to collaborate with the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke, the Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center, and Dr. Gerald Taiaiake Alfred on the vital work of collecting and preserving oral histories that reflect the lived experiences, cultural teachings, and perspectives of community members from Kahnawà:ke.

Ni’n Aq No’kmaq Genealogy Project

In October 2025, we traveled to Epekwitk (PEI) to speak with community members directly concerning connections built out for L’nuey’s Ni’n Aq No’kmaq Genealogy Project.