Dark Tourism: Canadian Residential Schools through the European Model

Dark Tourism: Canadian Residential Schools through the European model

This piece was written by our KH Associate Paige Foley, based in our Calgary Office. February 28th, 2019, the Military Museums of Calgary hosted a lecture on dark tourism. Below is Paige’s reflection on the event.

Last month, I attended a lecture put on by the Military Museums in relation to their current Founders Gallery exhibition, “Walled Off: The Politics of Containment.” Curated by Dona Schwartz of the University of Calgary, the exhibition utilizes the medium of photography to explore themes of, “state suppression, control and containment,” across several international case studies.

A surprising departure from the Military Museums’ regular programming, Jackie Jansen van Doorn’s presentation delved into Canada’s troubled relationship with its own history of containment during the lengthy Indian Residential School era. Through a lecture entitled, Dark Tourism: Canadian Residential Schools through the European model, Jansen van Doorn illuminated the ways in which dark tourism has largely become a framework through which various European countries have been able to reconcile with some of the darkest chapters of their history; and furthermore, puts forth that this European framework could provide a basis on which to create meaningful and sustainable progresses towards reconciliation in Canada.

So, what exactly is dark tourism?

At its most simplistic, the term ‘dark tourism’ has become an umbrella term for sites associated with death, suffering and human tragedy. As Jansen van Doorn suggests, dark tourism can range from sites and activities loosely based in history – such as ghost tours and dungeon tours, to places firmly dedicated to portraying an authentic glimpse into the past. In particular, the term ‘dark tourism’ has largely become associated with the Holocaust, comprising of the former camps and other related sites which have been preserved, or at times replicated, and can therefore typically claim a large degree of historical accuracy and authenticity.

Though Jansen van Doorn stresses the difficulty of ascertaining the precise motivations of the dark tourist demographic – and indeed, the ethical angle of dark tourism remains a lively discussion – she puts forth that a significant portion of those who go to places associated with death and suffering are in search of a transformative experience.

When it comes to histories of trauma, death and violence, dark tourism sites offer survivors and relatives a place of pilgrimage; for those without a direct personal or familial connection to the events, scholars suggest that dark tourism sites offer the opportunity to, “make sense of the historical heritage encountered, by making use of the material substance presented, the events and the people associated with it.”[i] In this way, many argue that dark tourism offers a viable alternative to the more traditional ways of learning about the past.

St. Michael’s Indian Residential School entrance, with two students on the driveway, Alert Bay, British Columbia, ca. 1970. Credit: Department of Citizenship and Immigration- Information Division / Library and Archives Canada / PA-185533

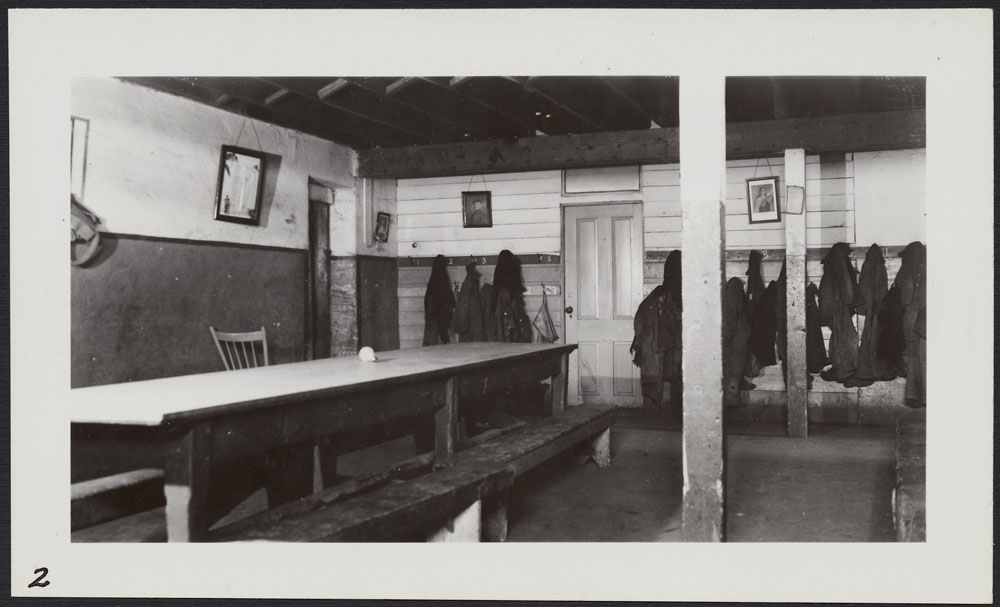

Recreation and dining hall on main floor, looking east, Ermineskin Indian Residential School, Hobbema, Alberta, June 3, 1938. Credit: Canada. Dept. Indian and Northern Affairs / Library and Archives Canada / e011080288.

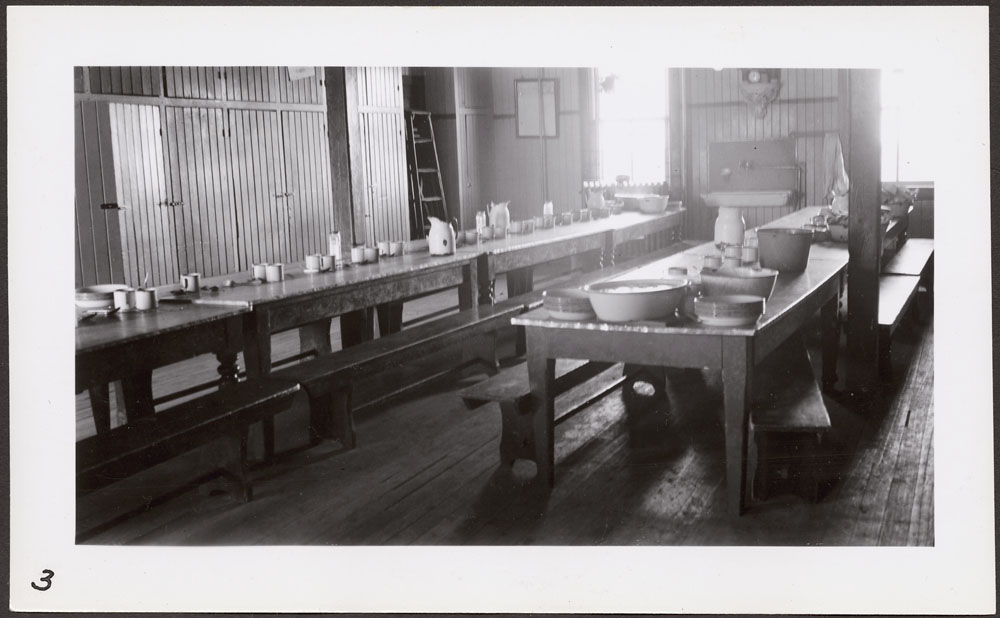

Recreation and dining hall in basement, looking west, Ermineskin Indian Residential School, Hobbema, Alberta, June 3, 1938. Credit: Canada. Dept. Indian and Northern Affairs / Library and Archives Canada / e011080289

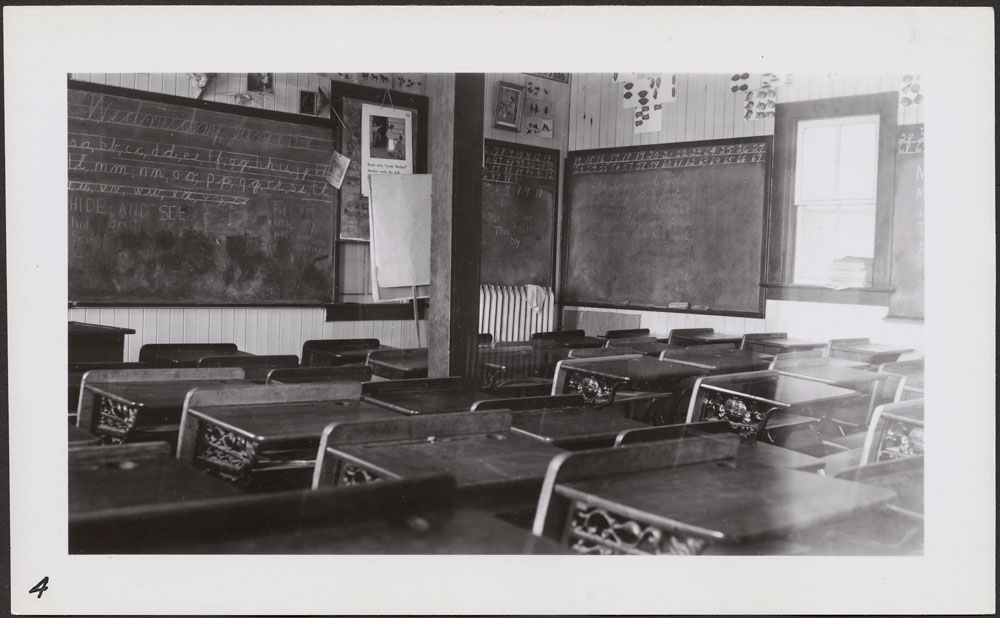

Grade 1 classroom on main floor, looking southwest, Ermineskin Indian Residential School, Hobbema, Alberta, June 3, 1938. Credit: Canada. Dept. Indian and Northern Affairs / Library and Archives Canada / e011080287

Jansen van Doorn proposes that the principles of dark tourism as understood through the European model can be applied within Canada’s heritage framework, advising that the musealization of former residential school buildings could offer a similarly transformative experience to Canadians in the climate of reconciliation.

While the intangible legacy of the Indian Residential School era is undeniably present across the nation, there is little remaining trace of the more than 130 residential schools that once operated in Canada. Jansen van Doorn suggests that there are perhaps less than 20 buildings from this period still in existence and fewer still which have not been repurposed. Moreover, only a small handful of these former buildings and related sites exhibit plaques or memorials.

It’s worth noting that actions are presently being taken to preserve these last remaining lieux de mémoire, or sites of memory,[i] by various Indigenous communities across the country. Most recently, efforts have been made to restore the former Mohawk Institute, a residential school for Six Nations children, operating in Brantford, Ontario from 1828 to 1970; on the other side of the coin, there are many others that consider these tangible reminders of the IRS era as too painful to persist and welcome their relegation to history. St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Alert Bay, British Columbia – operating from 1929 to 1974 – was notably demolished in 2015- a move largely supported by survivors and their relatives. Indeed, during the Q&A portion of Jansen van Doorn’s lecture, some audience members speculated that the preservation or renovation of the former schools could negatively affect those still suffering from a great deal of trauma.

Though it might be too early to predict the future, or perhaps lack thereof, of dark tourism within Canada, Jansen van Doorn’s lecture provides a great deal of insight into larger themes of commemoration and memorialization, nonetheless. Personally, I came away from the lecture reminded of Michael Rothberg’s concept of ‘multidirectional memory;’ a notion which suggests that the global memory of the Holocaust has, “enabled the articulation of other histories of victimization.”[ii] With that in mind, it seems logical that looking towards the European approach to dissonant heritage could prove useful in the journey towards reconciliation here in Canada.

Cover Image: Northwest view of school, St. Cyprian’s Indian Residential School, Brocket, Alberta, July 14-15, 1941. Credit: Canada. Dept. Indian and Northern Affairs / Library and Archives Canada / e011080323_s1

[i] Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations, No. 26 (1989): 7.[ii] Michael Rothberg, “Introduction: Theorizing Multidirectional Memory in a Transnational Age,” in Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization, 6.[i] Roxanna Magee and Audrey Gilmore, “Heritage site management: from dark tourism to transformative service experience?” The Service Industries Journal, 15-16 (2015): 902.

Recent Posts

Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke

We are proud to collaborate with the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke, the Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center, and Dr. Gerald Taiaiake Alfred on the vital work of collecting and preserving oral histories that reflect the lived experiences, cultural teachings, and perspectives of community members from Kahnawà:ke.

Ni’n Aq No’kmaq Genealogy Project

In October 2025, we traveled to Epekwitk (PEI) to speak with community members directly concerning connections built out for L’nuey’s Ni’n Aq No’kmaq Genealogy Project.

The Survivor’s Circle for Reproductive Justice

We were honored to attend the launch of the SCRJ’s report titled “Assisted Reproductive Services to Restore Fertility for Forcibly-Sterilized Indigenous Survivors: Options and Costs”.