“The number of the dead was so great”: Métis accounts of the 1870 smallpox epidemic on the prairies

“The number of the dead was so great”: Métis accounts of the 1870 smallpox epidemic on the prairies

This piece is the result of a collaborative effort from our team! Thanks go to Sara Wilmshurst, who wrote the main body of the article, with feedback from Alice Glaze, Nicole Marion-Patola, and Anna Kuntz. Research was also conducted by Sara, Alice, Nicole, Anna, and Paige Foley.

You do not need to be a historian to know that smallpox is woven into the story of North American colonization. The first outbreak in present-day Canada was in 1616, when First Nations communities near Tadoussac caught the disease from French fur traders.[1] For the next several centuries smallpox would terrorize indigenous peoples, killing many, scarring and blinding survivors, and dispersing communities.[2]

Smallpox was a virulent pathogen that could live on corpses and dry goods for weeks and travel from place to place on symptomless but highly contagious travelers.[3] In unexposed populations smallpox could cause mortality rates as high as 70%.[4] Even though survivors were immune for the rest of their lives, their descendants remained vulnerable without vaccination.[5]

Accordingly, every 50 years or so, the First Nations and Métis people on the Canadian prairies were ravaged by smallpox. The first epidemic on the Prairies travelled north from Spanish colonies with Snake traders in 1780, then the disease followed a similar path up the Missouri River in 1837, reaching the plains in 1838.[6] William Todd of the HBC, a smallpox survivor himself, vaccinated as many First Nations people as he could and met some success.[7] Paul Hackett estimates that, by late 1839, the majority of people living “from Lake Huron to the Pacific and from the American territory to the Arctic, were immune to smallpox” through immunization or natural exposure.[8] The next generations, though, went without vaccination and were vulnerable in 1870 when, yet again, smallpox came up the Missouri on the steamship Utah.[9] That outbreak killed an estimated 3512 First Nations and Métis people before burning out in October 1870.[10]

Several researchers have discussed this smallpox outbreak, but Métis voices are rarely heard in the scholarship. Juliette Champagne did excellent work reconstructing burial patterns, largely basing her work on Father Vital Fourmond’s letter to the Oblates’ periodical. Father Fourmond witnessed the epidemic first-hand when he joined a Métis hunting party out of St. Albert. He presided over dozens of burials at Pretty Hill and Lac Demay. Champagne also drew from interviews with a survivor, Jean Baptiste Lapointe (Peokis), providing one valuable Métis perspective.[11] James Daschuk leaned heavily on HBC sources, including reports, letters, and diaries.[12] It is challenging to collect the historic Métis perspective as most members of the community were illiterate. However, we have some access to their voices in scrip records.

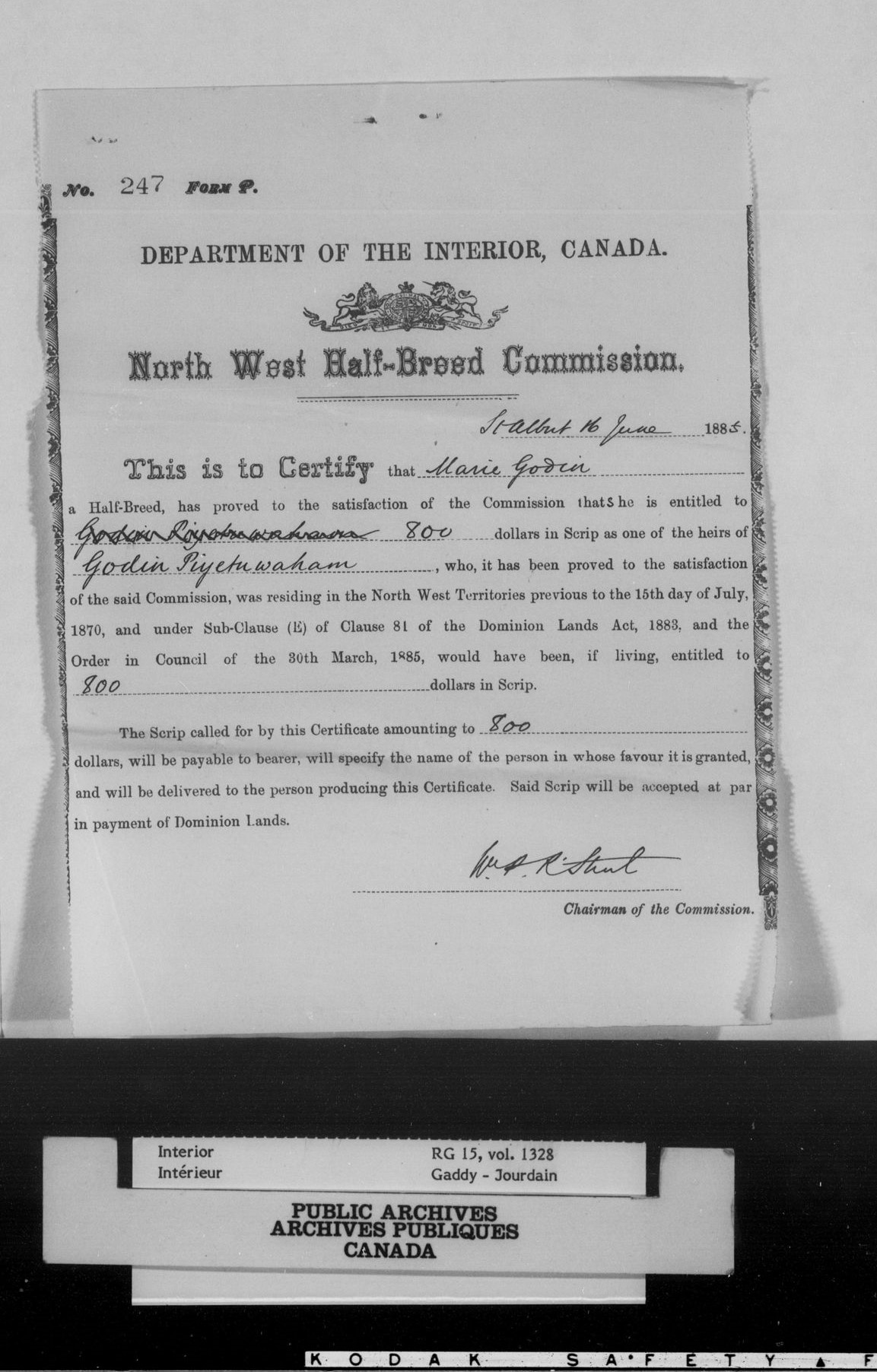

In 1885, the Canadian Department of the Interior extended its Northwest scrip program into present-day Alberta, Saskatchewan and northern Manitoba, having already offered scrip to the Métis of southern Manitoba in extinguishment of their aboriginal title.[13] If an applicant attested that they were a “halfbreed” of the Northwest Territories, they were entitled to $160 or $240 in cash, or 160 or 240 acres of land.[14] Scrip applicants and their witnesses made their case before a scrip commissioner, whose secretary recorded their (often translated) answers to questions and their additional comments. Scrip applications offer a filtered version of the applicant’s voice, to be sure, but for many Métis people this is all that has survived in writing.

In the scrip records for the Métis communities of central Alberta, the smallpox outbreak of 1870 looms large. Applicants at the 1885 and 1886 scrip commissions had to prove that they were resident in Rupert’s Land on 15 July 1870, when the territory’s ownership switched from the Hudson’s Bay Company to the Canadian government.[15] Many applicants referred to this as “the year of the transfer.” A significant subset of them, though, called it “the year of the smallpox.”

The summer and fall of 1870 were etched in community memory as the time of smallpox. Cecile Durand explained that she “was living with my sister near Lake St Anne for many years before and after the smallpox in 1870.”[16] When William and Peter Ward witnessed Antoine Hamelin Jr’s application, they specified that “we have known both father and son for many years before the smallpox.”[17] Moise Hamelin explained his family’s pattern of residence, including “2 years when my mother spend travelling to and from Great Slave Lake about the time of the smallpox.”[18] Charles Bateau Kwenis enumerated his deceased children; Francois died “about 3 years after the smallpox,” while Flora died “the 2nd summer after the smallpox.”[19] It wasn’t a time of total devastation, however. Elizabeth Donald’s parents remembered that she “was born in the Spring of the year of the smallpox.”[20]

Since scrip applicants could apply as heirs of their deceased relatives, scrip records show the devastation smallpox wrought in families. Eliza Petit Couteau or Piyesimwop, a mother of seven, died in St. Albert and was buried in the churchyard on 31 August 1870. Her widower Joseph Bruneau gathered his children and went “to the prairie to escape the smallpox,” but they could not outrun the disease. Joseph Bruneau and all but one of his children died and were interred on the prairie in the fall of 1870, leaving the sole survivor, Eliza Bruneau, to recount her story to the scrip commissioners.[21]

Marie Godin approached the commission on behalf of her late sister Genevieve, who “died at St Albert on the 10 September 1870 aged 18 years, intestate, leaving as her heirs her father + one sister + two brothers who all died with small pox, intestate and leaving as sole heir myself…My sister never was married but got an illegitimate son named Jean Baptiste he died after his mother in 1870.”[22]

Others explain how they became heirs in the first place due to smallpox. Catherine Chatelain, applying on behalf of her late son Joseph Desjarlais, detailed that Joseph died of smallpox in 1870, “leaving as heir his said father Pierre Desjarlais who died subsequently in the same fall 1870, intestate leaving as heirs, his widow the present deponent + his daughter Nancy Desjarlais who also subsequently died in 1870 intestate and without issue leaving a sole heir her mother the present deponent.”[23]

These are just examples; few if any of St. Albert’s Métis families moved through the 1870 smallpox outbreak unscathed. Over the summer and fall of 1870, St. Albert’s Métis population fell by 37%.[24] Of the 900 people in St. Albert, two-thirds were infected and 335 died.[25] Some died at home, while others passed away hunting on the plains and were buried in mass graves at Pretty Hill and Lac Demay.[26]

This sudden contraction in the population coincided with a period of great upheaval for Métis communities. Indeed, Paul Hackett argues that the Red River Resistance was a contributing cause: the HBC usually rushed to immunize First Nations and Métis people once outbreaks began, but supply chains broke down during the uprising and could not carry enough vaccine to the Prairies.[27]

It is also notable that the Métis population of the Prairies shrunk just before the numbered treaties and the Northwest scrip program legally defined the Métis. St. Albert fell within Treaty 6, which took effect in 1876.[28] By 1885, many “treaty Indians” decided to resign from treaty and seek scrip as “Northwest halfbreeds.”[29] Others, who had never been in treaty, applied for scrip and received, with it, a legal record of their Métis identity.

Scrip applicants in St. Albert reported horrific losses in the 1870 smallpox outbreak. At the same time, they asserted their embattled identities and added their stories to the written record. Most importantly, amid political challenges, the march of colonization, and a catastrophic epidemic, they survived.

[1] Christopher J. Rutty, “A Pox on our Nation,” Canada’s History 95, no. 1 (February/March 2015): 29.

[2] Rutty, “A Pox on our Nation,” 29-32.

[3] Maureen K. Lux, Medicine that Walks: Disease, Medicine, and Canadian Plains Native People, 1880-1940 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 14.

[4] James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013.), 12.

[5] Lux, Medicine that Walks, 15.

[6] C. Stuart Houston and Stan Houston, “The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders’ words,” Canadian Journal of Infectious Disease 11, no. 2 (March/April 2000): 112-113; Lux, Medicine that Walks, 15.

[7] Lux, Medicine that Walks, 15; Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 68.

[8] Paul Hackett, “Averting Disaster: The Hudson’s Bay Company and Smallpox in Western Canada during the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 78, no. 3 (Fall 2004): 606.

[9] Hackett, “Averting Disaster”, 608-609; Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 80-82.

[10] Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 82

[11] Juliette Champagne, “The Smallpox Epidemic of 1870: The Jolie Butte and Lac Demay Graveyards,” Alberta History 66, no. 3 (Summer 2018): p2+.

[12] Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 79-91.

[13] Melanie Niemi-Bohun, “Colonial Categories and Familial Responses to Treaty and Metis Scrip Policy: The ‘Edmonton and District Stragglers,’ 1870-88,” Canadian Historical Review 90, no. 1 (March 2009), 72, 78.

[14] Rupertsland Centre for Métis Research and Métis Nation of Alberta, Métis Scrip in Alberta, 2018, http://albertametis.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/RCMR-Scrip-Booklet-2018-150dpi.pdf.

[15] Rupertsland Centre for Métis Research and Métis Nation of Alberta, Métis Scrip in Alberta.

[16] Scrip application of Cecile Durand, 25 June 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1327, copied container number: C-14938, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[17] Scrip application of Antoine Hamelin Jr, 23 June 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1328, copied container number: C-14939, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[18] Scrip application of Moise Hamelin, 24 June 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1328, copied container number: C-14939, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[19] Scrip application of Charles Bateau Kwenis for his deceased son Francois Kwenis, 13 July 1886, RG15-D-II-8-c, volume/box number: 1352, copied container number: C-14979, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca); Scrip application of Charles Bateau Kwenis for his deceased daughter Flora, 13 July 1886, RG15-D-II-8-c, volume/box number: 1352, copied container number: C-14979, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[20] Scrip application of Elizabeth Donald, 1 July 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1327, copied container number: C-14938, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[21] Scrip application of Eliza Bruneau for deceased members of her family, 18 July 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1325, copied container number: C-14936, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[22] Scrip application of Marie Godin for deceased members of her family. 16 June 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1328, copied container number: C-14938, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[23] Scrip application of Catherine Chatelain for her deceased son Joseph Desjarlais, 19 July 1886, RG15-D-II-8-c, volume/box number: 1341, copied container number: C-14959, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

[24] Champagne, “The Smallpox Epidemic of 1870”.

[25] Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 82, 88.

[26] Juliette Champagne, “The Smallpox Epidemic of 1870”.

[27] Hackett, “Averting Disaster,” 608-609.

[28] Michelle Filice, “Treaty 6”, The Canadian Encyclopedia (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/treaty-6/) 10 November 2016 (accessed 25 August 2018).

[29] Neimi-Bohun, “Colonial Categories and Familial Responses to Treaty and Métis Scrip Policy,” 72.

Scrip application of Marie Godin for deceased members of her family. 16 June 1885, RG15-D-II-8-b, volume/box number: 1328, copied container number: C-14938, North-West Territories Métis scrip applications, Library and Archives Canada (via heritage.canadiana.ca).

Recent Posts

American Alliance of Museums Annual Meeting and Expo

We were pleased and honoured to have represented KH in Los Angeles, and to have demonstrated support for our American colleagues via our thoughtful, effective museums campaign.

Know History at the 2025 MUSEUMS CANADA Annual Summit

Know History was proud to be a Sustaining Partner of the 2025 MUSEUMS CANADA / MUSÉES CANADA Annual Summit, a national conference that brought together museum professionals, historians, and cultural leaders from across the country.

Meet Me Mondays: A Behind-the-Scenes Hit

Our Meet Me Monday series took social media by storm in 2025! Over the past few weeks, we’ve received fantastic feedback while highlighting some of the incredible colleagues who make Know History what it is.